David Gale’s Peachy Coochy Nites #2

20 slides are each projected for 20 seconds and spoken to for the same period, no more, no less. The script for one of these precision-based presentations is found below.

Season 1: PC#2

I realised that I was suffering from a fear of bursting. Some months ago a friend had been performing a yoga posture in the quietness of his front room. Without warning his intestines rushed from his body and coiled on the floor before him. Despite the enduring serenity he claimed to have achieved thereby, I saw myself become uncharacteristically chastened and cautious.

Everything around me seemed distended. Things thought thin now oozed uneasy bloat. Mere tautness to the touch portended splishsplash. Surfaces seemed to seep, to suppurate. I flinched in parks as flamboyant gesticulators inflated then shrugged or softly smiled. Envelopes groaned, sausages mocked me.

I lived in a small house in North London. The street was secluded and little traffic passed along it. Most of us in the street read the work of Dick Francis although we did not discuss it. House hedges were high but used volumes were left on low walls for communal exchange. I had just finished the 1972 tour de force ‘Smokescreen’ and hoped to acquire 1973’s ‘Slayride’.

Preoccupied with my preoccupations I rose that day and made my way along my street. Dick’s works were laid out as usual. I had read them all. Towards the end of the street I spotted an unfamiliar jacket. At first I assumed it was a Dick because the first two letters of the surname were the same. “Dick…Freud. Who is that?” I wondered. I picked up the volume and examined it.

I read the book from cover to cover, initially under the impression that it was a pseudonymous racing mystery with a theme of prediction. I gradually realised that, in fact, it contained a very interesting theory. Apparently, at least in Freud’s view, there was a vast hidden world buried deep inside every one of us. Why had no one in the street mentioned this?

The book had been translated into English in 1913. The relative obscurity of my street meant that the translation had not become available until 2007. This would explain why I was so poorly informed. I knew, however, that I must now, without further delay, do something that would reshape my life and stop me bursting. I wanted a subconscious and nothing would stand in my way.

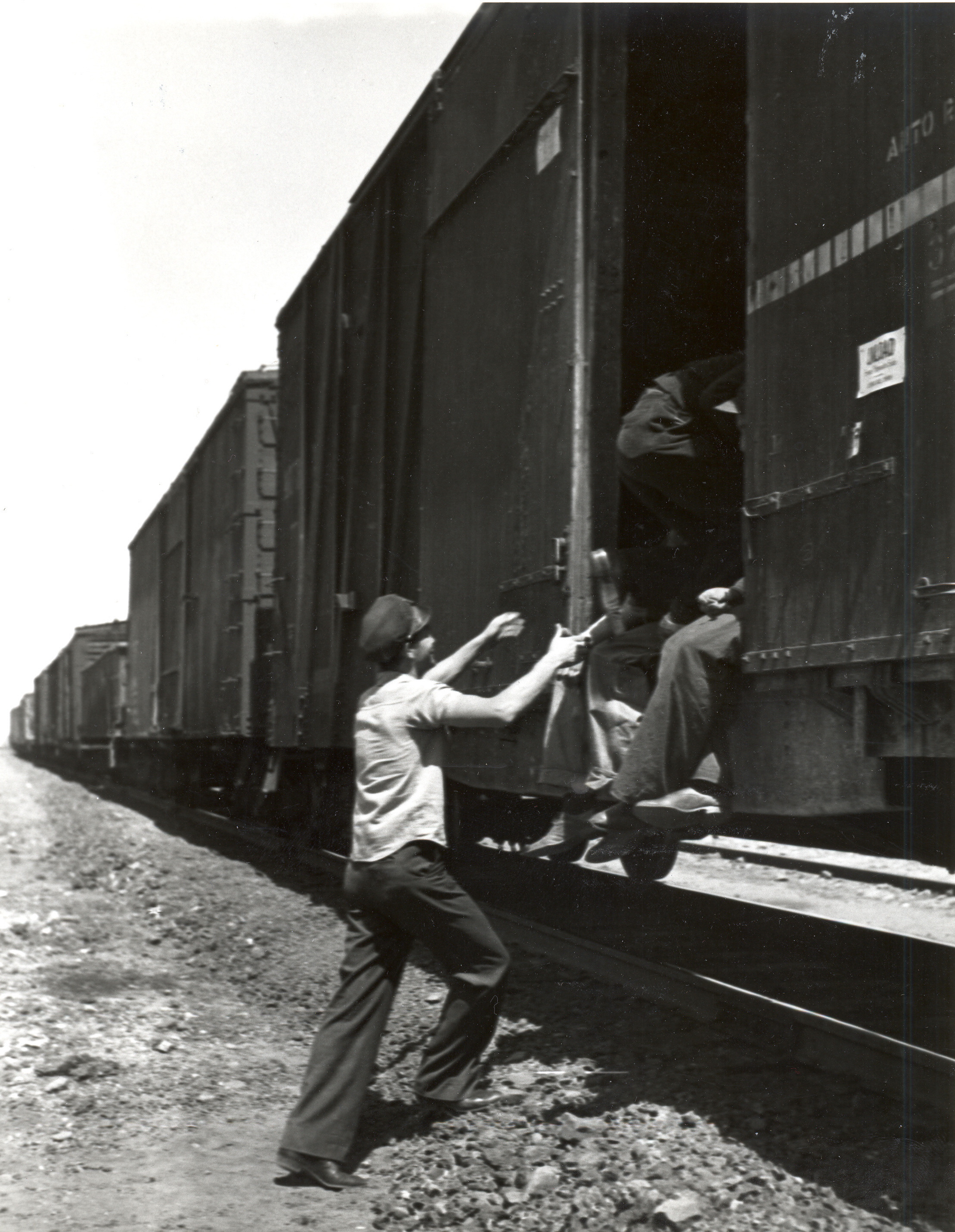

I left my street, taking some some fish paste sandwiches, a dictionary and a cassette player. Where would I go to get a subconscious? I passed a number of imposing towers and these somehow stiffened my resolve. I had a choice: either I could head into the dense bush in the hope of finding a mound or I could consult a passerby.

As luck would have it I came upon a most accommodating fellow. “How might I obtain a subconscious?” I asked him. “Fuckingpigsarse! Fuckingduckshit! They’re all fucking smiling now but he’ll come down if you ask him! Come on puss, come on, you fucking belligeranti, you fucking warwound! Fuckyourmother! Fuckyourmother!”

So I went to see the Queen. She was relaxing in her Royal Room. I bowed low and told her what the red-headed man had said. “Yeah,” she said “if you go with me it will certainly make things easier for you.” The Queen lay very still and shouted royal messages “This is my throne, this is my ermine, this is my sceptre, you are all vermin.” I went blind.

Nurse, nurse! She opened her purse and my eyes have burst. In the park in the dark. My eyes have burst. I’m cursed. I’m immersed. All taut gone slop. All night gone shite. All night now. Who seeks shall find; Who sits with folded hands or sleeps is blind. I miss the sweetest sight, my parents’ face.

Benny! Benny! Benny! etc

Down the deep creeks creak sheep. Flying fences in their sleep. Stifled with a muffle. The engine rooms are just intolerable. Wrap some towel round that, would you? They were soft, like grapes – we cut them out. We heard a tapping. On a pipe. With a spoon. Or a knife.

Then I saw my parents again. Len, Joan, Joan and Len. I had to move them apart. I got between Joan and Joan for the first time ever. I went between them and pushed and pushed. There was a crack. They kept holding on to Len and Len but I broke my mothers in two. Joan and Len then Joan and Len. The sky opened up and things came down.

Oh now! Jimmy Croc Cow! Jimmy Croc Cow and I don’t care. Dogcheese, catalept, pigment, turvy tops and tails, in through the out door. Well, I don’t know, Margaret, I opened the curtains and people were relieving themselves in the street! It was awash with ones and twos! The fucking stench! Men with banjos were speaking with their mouths full!

She went to the cupboard and I was bare. Then she opened it. Then she ran her hands over the shelves. Her little dog barked. I screamed out because those shelves were so sensitive – I could feel her fingertips, they were rough. Doesn’t she know those things are inside me? Doesn’t she know I’ve eaten the world and I’m a naughty boy?

“It was getting silly.” I either had to swallow or puke. If I swallowed then I would shit – I’d shit the world out. If I puked then the world would not be so harmed. It would come out more or less in decent condition, none the worse for its days in my stomach. The only problem was not knowing what order it would come out in.

I moved my legs apart slightly to give myself a stable footing and stood between two parallel bars that I had noticed nearby. I grasped the bars and, thus braced, took a deep breath. The world felt heavy but I knew I could do it. I opened my mouth wide and contracted my diaphragm forcefully. Suddenly the world was in space again. I jumped down onto it.

The very first thing I did was to go and see Celine Dion. We had met in Morrisons and become friendly. I found her down to earth and easy to be with. Celine quoted from Guy Debord, the Situationist writer, of whom she was very fond. They had been neighbours when she was a little girl.

“You see, David, “ Celine said, “The spectacle is not a collection of images, rather, it is a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.” “But, Celine,” I confessed, “I fear the sheer, engulfing volume of it all. It floods into me until I can hardly bear it.” Celine grew serious “David, listen to me. Your fear of bursting is over now. Once you’ve puked the world you can do what you fucking want.”

I didn’t go back home. I felt light. I felt effective. I discovered that you don’t have to have a subconscious – it’s just an idea. I met some people who were cognitive behavioural therapists – they confirmed this. They said it was all to do with changing mental images. If you have an image inside you you don’t like, you can change it. It’s all to do with images.